Researchers sometimes wonder if they should, or even could, start broadcasting or writing about science. Is it possible to take leave of the lab and become a science communicator?

This was the question uppermost in the minds of science postdocs at Queen’s this month when they gathered to hear what a panel of experienced science journalists had to say about what they do and how they had first entered the field.

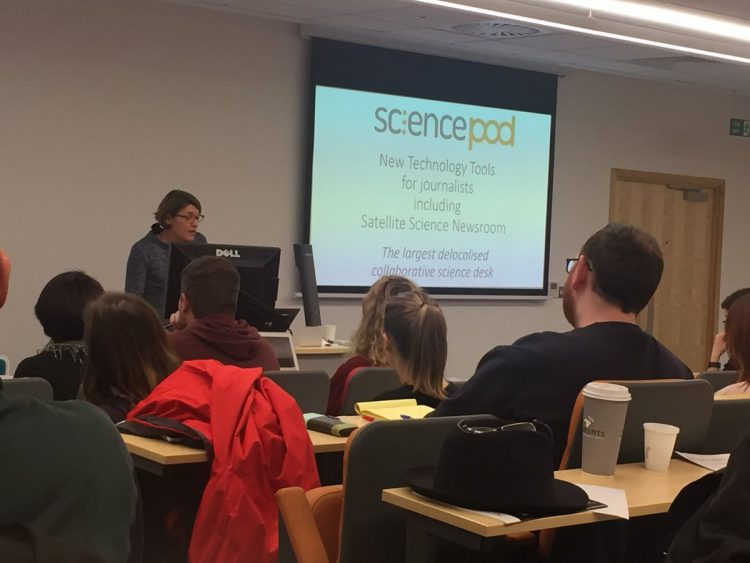

The workshop, organised jointly by the Irish Science and Technology Journalists’ Association (ISTJA) and the Association of British Science Writers (ABSW) and hosted by the Centre for Experimental Medicine at Queen’s, had an impressive line up of writers and broadcasters, all ready to share their knowledge and give the postdocs tips on how to carve out a niche in the highly competitive world of communications.

As the postdocs were told, they are already well on the road to become a communicator because they can get going with two distinct advantages, in-depth knowledge of science and a command of English.

Sabine Louet who once worked as a news editor with Nature, commented that changing over from her native French to English had given her journalistic career a considerable boost.

Having a hands-on knowledge of science gives a journalist a considerable edge over those who are unlikely to understand the concepts or have the ability to unravel the arcane peer-to-peer code used between scientists. When asked for advice on how to get into communications, this writer said that the science should always come first, and only then the writing.

The term ‘science communications’ is often assumed to embrace, or even be the same as science journalism, but as everyone on the panel agreed, simply lumping the two together is a serious but widespread error. While the term ‘communications’ usually refers to such activities as outreach, managed content or PR, science journalists fight hard to maintain their independence.

The panel members stressed the importance of this distinction because journalists, unlike communicators, have a vital role to play in presenting the public with unbiased content. A person employed as a communicator is always obliged to present a positive view, and scientists have been known to lie, claiming to be right, when they are, in fact, wrong. If only to have a well-informed society, independent science journalists are needed to cover important issues by raising questions and asking for second opinions.

Post-grads, of course, are free to make their choices between entering the relatively cozy, and often well-paid world of managed communications, or embarking on the more difficult path into science journalism.

As talented journalist such as Claire O’Connell, Leo Enright or Anthony King could demonstrate, it is possible to follow this freelance route and thrive. How each of these journalists and the others on the panel had successfully broken into the field is, in each case, a completely different story.

As the long-established broadcaster, Leo Enright, recalled, his high profile as space correspondent all began when he had the good luck to get a press pass enabling him to report back on the Moon mission launch.

Marine scientist, Olive Heffernan, got hooked on journalism when Seán Duke asked her to write up a report in Science Spin, and Maria Delaney, 2015 winner of the ABSW Newcomer Award for Britain and Ireland, started off by writing a blog. Writing the blog, she said, was relatively easy to do and it gave her the confidence to plunge into the wider field of journalism. Editors spotted the exceptional quality of her reporting leading on to features in The Sunday Times, Guardian and other papers.

Emma Stoye, a senior science correspondent with Chemistry World, got her break working as an intern for the Naked Scientist Show. Marie Boran, who writes a weekly column in The Irish Times is one of the few that began with a PhD from Dublin City University in science communications (more info here). Claire O’Connell, a regular contributor to the Irish Times, had been following a brilliant research career when she decided that journalism was a more attractive option.

Like Anthony King, whose work regularly features in Irish and international publications, Claire keeps a lot of irons in the fire. Both said that they would have lots of stories on the go, ready to finish up on getting an editorial go-ahead. Their advice to aspiring writers is not to put all their eggs in the one basket, get to know what editors want, and before finishing an article, submit an outline first. Also, new writers should not be overcome by disappointment if their initial offerings are turned down, or worse, ignored. There can be all sorts of reasons for rejection, no space, no money, or even too busy.

To contact the Irish Science and Technology Journalists’ Association: anthonyjking@gmail.com

For more about the Association of British Science Writers: https://www.absw.org.uk

On the panel: Marie Boran, Claire O’Connell, Maria Delaney, Leo Enright, Olive Heffernan, Tom Kennedy, Anthony King, Sabine Louet and Emma Stoye. With thanks to the organizers, Dr Lindsay Broadbent, Dr Alice Dubois, Dr Amy Dumingan, Dr Joana Sa Pessoa and Mico Tatalovic.

Article By Tom Kennedy – 24th October 2017

This article was first posted on sciencespin.com http://sciencespin.com/talking-about-science/